The strike at the British Aerospace factory in Kingston, November 1989 to April 1990

BAe workers march past the new bus station in Kingston, 31st January 1990

The strike began on 15 November 1989, and lasted until 25 April 1990. The strike was called as part of a national campaign for a 35-hour week in British industry, in place of the existing 39-hour week. The Kingston site was one of just a handful targeted throughout the country. Others firms reached agreement and were fairly soon back at work, but the BAe action in Kingston continued for over five months.

The Surrey Comet reported the beginning of the strike on the front page of its edition of 17 November, noting some confusion because the night shift was the first affected, and some workers went in to work anyway. However by Thursday morning a picket line had been organised and a spokesman for the Confederation of Shipbuilding and Engineering Union (CSEU) claimed that almost all (“98%”) of the 1200 manual workers were respecting it. White collar workers, as members of other unions, disregarded the pickets and, on the whole, continued to work normally throughout.

The Surrey Comet reported the beginning of the strike on the front page of its edition of 17 November, noting some confusion because the night shift was the first affected, and some workers went in to work anyway. However by Thursday morning a picket line had been organised and a spokesman for the Confederation of Shipbuilding and Engineering Union (CSEU) claimed that almost all (“98%”) of the 1200 manual workers were respecting it. White collar workers, as members of other unions, disregarded the pickets and, on the whole, continued to work normally throughout.

At the end of the first complete week, the Surrey Comet on 24 November reported that the CSEU was claiming almost complete support for the strike, and encouragement from their members. The BAe management, however, pointed out that the main effect of the strike was to hurt BAe’s customers because their goods would not be delivered.

An offer was made to the strikers of a 37-hour week, to be in place by 1992, but was dismissed by the CSEU as inadequate. This was reported in the Surrey Comet in its issue of 1 December 1989 as “Strikers reject BAe’s offer”. Strike pay, provided from a levy on the wages of other union workers, had been £150 per week, but was reduced to £85 per week after four weeks

An offer was made to the strikers of a 37-hour week, to be in place by 1992, but was dismissed by the CSEU as inadequate. This was reported in the Surrey Comet in its issue of 1 December 1989 as “Strikers reject BAe’s offer”. Strike pay, provided from a levy on the wages of other union workers, had been £150 per week, but was reduced to £85 per week after four weeks

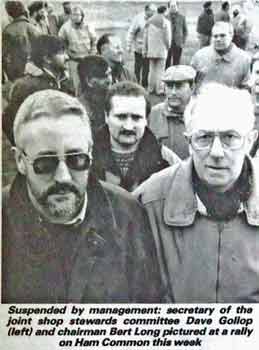

In December, as the supply of parts from Kingston to BAe’s Dunsfold factory began to dry up and workers there became idle, attempts were made to bus employees from Dunsfold to Kingston in accordance with their contracts. Alas, the workers refused to cross picket lines, and 12 Dunsfold men were therefore suspended by management.

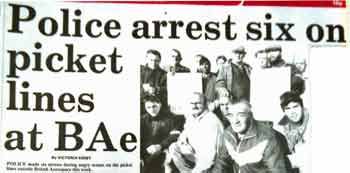

The strike does seem, on the whole, to have been well conducted. There was some provocative shouting of abuse, and half-a-dozen or so scuffles leading to arrests by the police, most of which resulted in a formal warning and release. There were allegations that some of those going in to work were finding their cars vandalised. But after a month the situation had established itself such that the police reported they were scaling down their presence.

The strike does seem, on the whole, to have been well conducted. There was some provocative shouting of abuse, and half-a-dozen or so scuffles leading to arrests by the police, most of which resulted in a formal warning and release. There were allegations that some of those going in to work were finding their cars vandalised. But after a month the situation had established itself such that the police reported they were scaling down their presence.

As Christmas approached, the Surrey Comet of 22 December 1989 contained only a brief reference that no settlement was in sight or expected. Both sides expressed willingness to talk, but BAe demanded a return to work first, something that the union refused to countenance.

As Christmas approached, the Surrey Comet of 22 December 1989 contained only a brief reference that no settlement was in sight or expected. Both sides expressed willingness to talk, but BAe demanded a return to work first, something that the union refused to countenance.

The new year, 1990, began with the situation unchanged except that the management could claim that over a hundred manual workers were now crossing the picket lines daily. However, as this was less than 10% of the workforce, the union representatives felt able to continue the strike.

In late January the Surrey Comet reported the involvement of ACAS (the Advisory Conciliation and Arbitration Service) and a faint hope of resolution of the dispute. For two issues of the Surrey Comet, the strike was not even mentioned, probably because of reporting the effects of the hurricane that swept through the area, lifting roofs, knocking trees over and sinking cabin cruisers in the River Thames. Life on the picket lines must have been pretty grim anyway without extra avoidable aggravation.

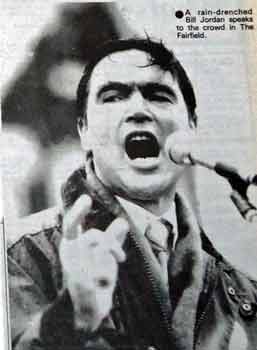

On 31 January a protest march through the centre of Kingston was attended by workers from some of the other BAe factories also on strike for the 35-hour week. However, the strike pickets must by then have become a part of the scenery because the Surrey Comet’s report of the protest march was on page 13 of the following week, – that is nine days later. Even the subsequent return to work at other BAe sites was not mentioned and, in fact it was eight weeks before the Surrey Comet referred to the strike on its front page again, when a low-key article headed “Bid to end air dispute” appeared near the bottom on 12 April. It reported another ACAS initiative to bring the two sides together.

On 31 January a protest march through the centre of Kingston was attended by workers from some of the other BAe factories also on strike for the 35-hour week. However, the strike pickets must by then have become a part of the scenery because the Surrey Comet’s report of the protest march was on page 13 of the following week, – that is nine days later. Even the subsequent return to work at other BAe sites was not mentioned and, in fact it was eight weeks before the Surrey Comet referred to the strike on its front page again, when a low-key article headed “Bid to end air dispute” appeared near the bottom on 12 April. It reported another ACAS initiative to bring the two sides together.

This brought the breakthrough: the two sides must have decided that enough was enough. After some face-saving haggling over details, the manual workers returned to work on Wednesday 25 April, and the five-month strike was over.

Some dissatisfaction was expressed by both sides and, twenty two years on, it does seem that the gains by the workers were little more than had been offered two months earlier when the other BAe sites went back to work, and that the management had lost considerable production time unnecessarily.

- In mid-January the BAe management at Kingston expressed some concern at the number of strikers who had grown disillusioned and had handed in their notice. “More than 30 …” had left the factory, and it is likely that they were skilled workers who would be difficult to replace.

- During the strike there had been several encouraging announcements showing that there was still a belief on the company’s products. On 9 March two orders for new aircraft came in, one from the RAF for 14 new trainers and from the RN for 10 Sea Harriers. Three weeks later, the Surrey Comet of 30 March reported record profits at the Kingston factory.

- During the week before the strike a model of a Sea Harrier had been stolen overnight from the canteen at the BAe factory where a display had been prepared for a ceremony on 3 November.

- In its edition of 30 March 1990, the Surrey Comet reported that BAe had presented the profits from a booklet, 75 Years of Aviation in Kingston, to the local hospital.